Research on Tooth Relics: History, Significance, and Scientific Studies

Abstract

Tooth relics are important objects in history and religion. They often come from famous people like the Buddha. This article looks at the history of the Buddha's tooth relic, its meaning in Buddhism, and how science studies ancient teeth. We use simple words to explain these ideas. The article has sections on history, culture, science, and a list of sources. It also includes pictures to help understand.

Introduction

What are tooth relics? A relic is a part of a person's body that people keep after death. It is special because it reminds them of that person. In Buddhism, tooth relics are very holy. The most famous one is the tooth of the Buddha. It is kept in Sri Lanka. People believe it gives power to rulers.

This article talks about research on tooth relics. We focus on the Buddha's tooth because it has a long history. We also look at how scientists study old teeth from the past. These teeth tell us about ancient people, their food, and where they came from. The information comes from books, websites, and studies.

Why study tooth relics? They help us learn about religion, culture, and science. In religion, they connect people to the past. In science, teeth are strong and last a long time. They give clues about human history.

This picture shows the Temple of the Tooth Relic in Kandy, Sri Lanka. It is where the famous tooth is kept.

History of the Buddha's Tooth Relic

The story of the Buddha's tooth starts long ago. The Buddha lived in India about 2,500 years ago. His real name was Siddhartha Gautama. After he died, people burned his body. From the fire, they found four teeth. These teeth became relics.

One tooth went to a king in India. Later, there was a war over it. People thought that if you have the tooth, you can rule the land. In the 4th century, a princess hid the tooth in her hair and brought it to Sri Lanka. The king there built a temple for it in Anuradhapura.

Over time, the tooth moved to different places in Sri Lanka. Kings always kept it near them. In the 16th century, it came to Kandy. The Portuguese tried to destroy it, but it survived. Today, it is in the Temple of the Tooth. Every year, there is a big festival called Esala Perahera. Elephants and dancers carry the relic in a parade.

There are other tooth relics too. One is in Singapore at the Buddha Tooth Relic Temple. It was found in Myanmar in 1980. A monk discovered it in an old stupa. Now, it is in a gold stupa for people to see.

Some people question if these teeth are real. But for Buddhists, they are symbols of faith. History books like the Mahaparinibbana Sutta talk about the teeth.

Here is another view of the temple. It shows the beautiful building where the relic is protected.

Significance in Culture and Religion

Why is the tooth relic important? In Buddhism, relics are like the Buddha is still here. They have spiritual power. People pray to them for blessings. In Sri Lanka, the tooth is a symbol of the country. The president takes care of it. It shows who has the right to rule.

In the past, kings fought for the relic. If you have it, gods approve you as leader. This idea came from India. When the tooth came to Sri Lanka, it helped unite the people.

Today, millions visit the temple. They bring flowers and pray. The relic helps keep Buddhist traditions alive. It also brings tourists to Sri Lanka. The temple has museums with old art and stories about the Buddha.

In other places, like Singapore, the temple teaches about Buddhism. It has classes and helps the community. The relic there is from a different tooth, but it has the same meaning.

Some relics are broken pieces. One book talks about a "Broken Front Tooth Relic" from Afghanistan. It is a small fragment in a silver box. It shows that even small parts are holy.

The relic connects people across countries. From India to Sri Lanka to Singapore, it spreads Buddhist ideas.

This image is of the inside of the temple. You can see the gold stupa that holds the tooth.

Scientific Research on Ancient Tooth Relics

Now, let's talk about science. Tooth relics are not just for religion. Scientists study old teeth to learn about the past. Teeth are hard and do not break easily. They stay in the ground for thousands of years.

In archaeology, teeth tell us about ancient people. For example, marks on teeth show what food they ate. If teeth have lines, it means the person was sick or hungry.

Scientists use DNA from teeth to find out where people came from. One study looked at old teeth and found that Native Americans came from Asia in one big group.

In some places, people removed teeth on purpose. In ancient Taiwan and Vietnam, they pulled out front teeth as a ritual. It showed they belonged to a group. This started 4,800 years ago. It helps us understand migration in Asia.

In Europe, Stone Age people used animal teeth for jewelry. Scientists tested ways to pull teeth from animals. They used cutting and heating.

For religious relics, some scientists check if they are real. They use X-rays or scans. One study looked at the Buddha's tooth in Sri Lanka. It said the tooth looks like a human canine tooth.

Teeth also show how people lived. In the Holy Land, old teeth help study diseases from the past.

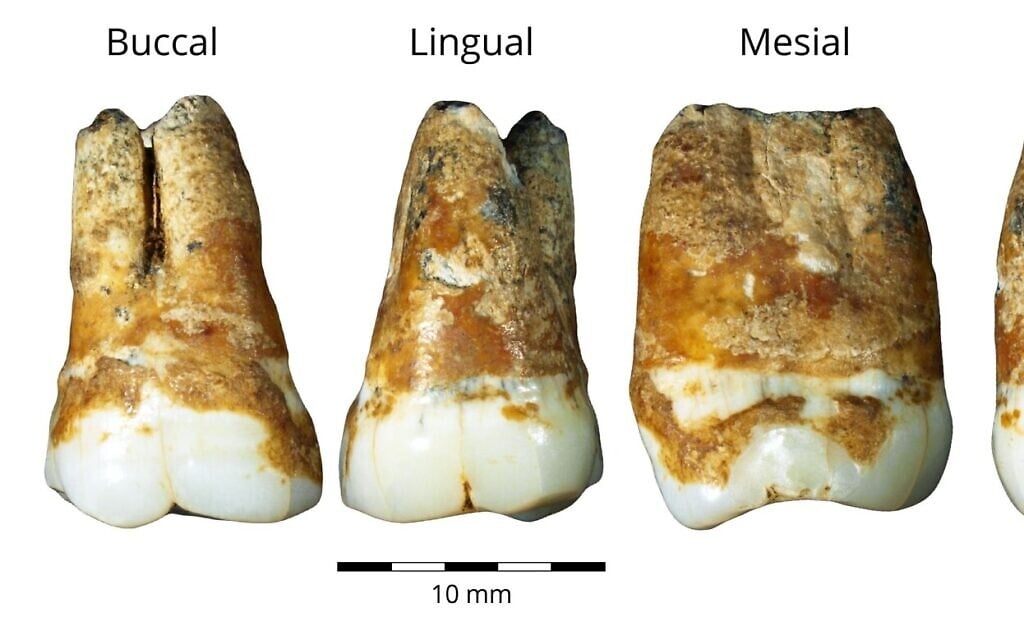

This photo shows ancient human teeth found in Israel. They help scientists learn about early humans.

More on Scientific Methods

Scientists use new tools to study teeth. They look at isotopes in teeth. These tell about diet and where the person grew up. For example, if someone ate a lot of plants, the teeth show it.

In forensics, teeth help identify people. But for ancient relics, it is about history. One book says teeth are "windows into the past."

In Turkey, 8,500 years ago, people wore human teeth as jewelry. This shows how teeth were important in culture.

Research on tooth relics mixes religion and science. For Buddha's tooth, history books tell the story, but science checks the facts.

Here is an ancient jaw with teeth. It helps study human migration.

Challenges in Research

Studying relics is not easy. Religious relics are holy, so scientists cannot always touch them. People may not allow tests. Also, some relics are fake. History has many stories of wars over them.

In archaeology, finding teeth is good, but they need careful cleaning. Weather and time can damage them.

Future research may use better technology. Like 3D scans or AI to study shapes.

This image shows human teeth used as jewelry from long ago.

Conclusion

Tooth relics are fascinating. The Buddha's tooth has a rich history from India to Sri Lanka. It means power and faith in religion. In science, ancient teeth teach us about human life, food, and travel.

Research helps us understand our past. It connects religion, culture, and science. More studies will find new stories from teeth.

We hope this article helps you learn about tooth relics in a simple way.

References

- The tooth relic of the Buddha: The viewpoint from paleodontology and modern dentistry - PMC - NIH. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10829713

- Relic of the tooth of the Buddha - Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Relic_of_the_tooth_of_the_Buddha

- Temple of the Tooth |History, Description, & Facts - Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Temple-of-the-Tooth

- The Buddha Tooth Relics: Special Research on the Broken Front Tooth Relics - PhilArchive. https://philarchive.org/archive/BHITBT

- How the Sacred Buddha's Tooth Relic & the Righteous Ruler of Sri Lanka are connected - LankaWeb. https://www.lankaweb.com/news/items/2025/04/12/how-the-sacred-buddhas-tooth-relic-the-righteous-ruler-of-sri-lanka-are-connected

- THE SWEET SACRED TOOTH OF KANDY: Buddha's tooth relic temple in Kandy - Dakini Translations. https://dakinitranslations.com/2024/03/20/a-sacred-tooth-of-kandy-buddhas-tooth-relic-temple-in-kandy-sri-lanka-pilgrimage-ii

- Buddha Tooth Relic Temple in Singapore: Sacred History & Visitor Guide - Mantrapiece. https://mantrapiece.com/blogs/famous-buddhist-temples/exploring-the-buddha-tooth-relic-temple-in-singapore

- (PDF) The Buddha Tooth Relics: Special Research on the Broken Front Tooth Relics - ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/399233357_The_Buddha_Tooth_Relics_Special_Research_on_the_Broken_Front_Tooth_Relics

- A history of the Tooth Relic in Ceylon - SOAS Repository. https://soas-repository.worktribe.com/output/405731/a-history-of-the-tooth-relic-in-ceylon-with-special-reference-to-its-political-significance-c-ad-300-1500

- Buddha Tooth Relic Temple and Museum - Singapore - NLB. https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=389e7067-97fb-4e1d-b7e9-688efd442319

- 15 Facts & Figures about the Buddha Tooth Relic Temple and Museum - Clio Muse Tours. https://cliomusetours.com/15-fun-facts-about-the-buddha-tooth-relic-temple-and-museum

- Windows into the past: recent scientific techniques in dental analysis - PMC. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10853062

- Ritual tooth ablation in ancient Taiwan and the Austronesian expansion - ScienceDirect. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352226724000448

- What Ancient Teeth Can Tell Us About Humanity's Past - University of Illinois Chicago. https://dentistry.uic.edu/news-stories/what-ancient-teeth-can-tell-us-about-humanitys-past

- Study of Ancient Teeth Shows Single Native American Migration from Asia - Ancient Origins. https://www.ancient-origins.net/news-evolution-human-origins/native-american-migration-0020088

- Marks of Belonging: What Tooth Removal Reveals About Ancient Migration and Identity in Vietnam - Anthropology.net. https://www.anthropology.net/p/marks-of-belonging-what-tooth-removal

- Study reveals Stone Age methods of extracting animal teeth for jewelry - The Jerusalem Post. https://www.jpost.com/archaeology/article-858777

.jpeg)